|

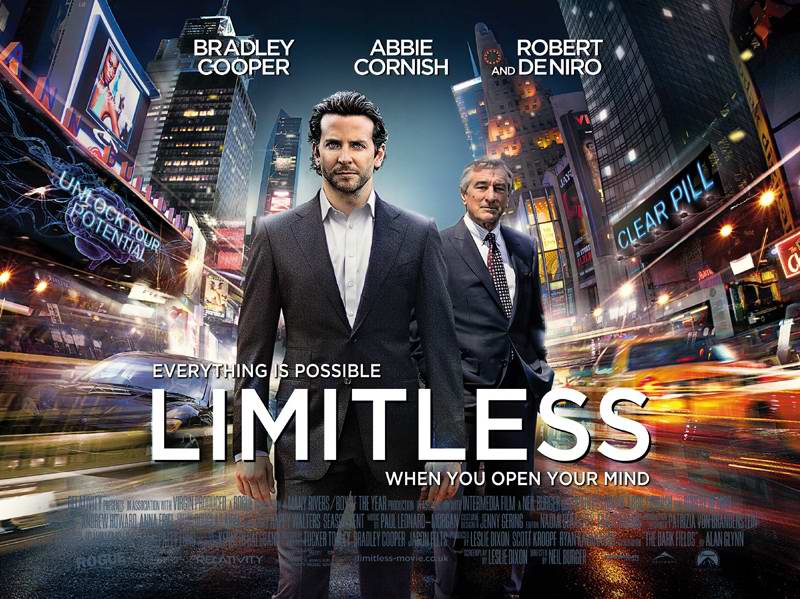

One of the students at my recent Writing Science Fiction workshop asked, "what is the definition of Science Fiction?" It’s a good question. A vast range of stories comes under this genre heading. Stories about aliens and robots. Post-apocalyptic stories and pre-apocalyptic stories. Time-travel stories, and ones that take place in alternative histories. Stories about the far future, and stories about the distant past. Epic “space operas” and small chamber pieces. Science Fiction covers a huge amount of ground - and not all of it has that much to do with science. So how do so many diverse themes fit into a single genre? One way to answer the question is to look at two films with similar themes and see what makes one Science Fiction, and the other … something else. In BIGGER THAN LIFE (Nicholas Ray, 1958), schoolteacher Ed Avery is prescribed cortisone for a heart condition. The drug has an unexpected side-effect: he becomes suffused with a sense of personal power, megalomaniacally convinced that he has “a special plan for this world,” which he retails to a mixed response at his school’s PTA evening. Later, feeling displeased with his son, Ed decides that he must deal with him in the manner of the biblical Abraham, who was ordered by God to sacrifice his own son, Isaac. Ed’s terrified wife reminds him that the Bible story was in the nature of a test: on seeing Abraham’s obedience, God relented and sent an angel to tell the faithful father to spare Isaac. Ed answers his wife with the memorable line, “God was wrong.” But the effects of the drug never really transcend Ed’s family and immediate surroundings, and we don’t feel that his estimation of his mental powers and leadership potential is accurate. It seems, instead, that he is horribly deluded. So Bigger Than Life remains a Social or Medical Drama – maybe a Psychodrama – rather than a Science Fiction story. Let’s compare LIMITLESS (Neil Burger, 2011). When struggling writer Eddie Morra begins to take a smart drug, his intelligence actually is elevated. He can write long screeds of quality prose without effort; he has instant, detailed access to all his memories, no matter how fleeting or partial; his perceptions become extremely acute; and he can quickly synthesise all these elements into expert knowledge on virtually any subject, enabling him to earn a fortune as a Wall Street trader - evidently the fastest route he can envisage to complete financial independence. In other words, the changes that the drug has made in Eddie are tested against a wider world – and found to be real. Later in the film, Eddie must contend with another man who is also taking the smart drug, and is using his increased capacity to the more sinister ends of masterminding a violent criminal empire. This is a strong sign that the drug is indeed effective, and that it can be put to a wide variety of applications. It’s possible to imagine a scenario in which the central conceit of Limitless is taken a step further, and just about everyone in a given society – or the world at large - has their intelligence and effectiveness raised by the drug. What would a planet full of individual geniuses, all pursuing their possibly conflicting ends, look like? That’s a question for another day, but Eddie and Ed’s experience suggests a possible working definition of Science Fiction: “A story with a novel (but plausible) twist on reality at its heart which has the potential to ripple out and affect the entire world in which the story is set.” Please let me know if you have any further thoughts on this – perhaps you can come up with a much better definition? I’ll be holding the Writing Science Fiction workshop again in the not-too-distant future – do get in touch if you would like to know more.

8 Comments

Sid Cup, from Sidcup

9/29/2015 08:04:31 pm

I think your suggested definition is, perhaps, a tad limiting.

Reply

Yes, this may be true - although, in those scenarios, isn't the twist on reality constituted by the very "positing of a futuristic world"?

Reply

Art Schlock

9/29/2015 10:45:33 pm

Kesteven hasn't really had the acclaim he deserves.

Ian

9/29/2015 10:54:08 pm

I take your general point, although I don't think my definition is too limiting, as most SF stories do use a twist of some kind - the ones that simply re-set an existing narrative in a future or alternative world are in a minority.

Reply

Erica Nerney

9/29/2015 11:18:34 pm

And I take YOUR general point. However, "most" isn't "all", and a proper definition should be all-embracing - the definition as it stands would exclude, for instance, J. Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, H.G. Wells's The First Men in the Moon, I. Asimov's Foundation Trilogy, A.C. Clarke's A Fall of Moondust, or even P.K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle.

Reply

Ian

9/30/2015 12:01:03 am

And just remind me, your definition is ..?

Reply

Ian

10/3/2015 04:49:13 pm

I just found another definition in David Pringle's book, Science Fiction The 100 Best Novels:

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI'm a screenwriter, script editor and graphic artist, and I also teach workshops on various aspects of screenwriting. Archives

November 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed